Rules for Writing Software Tutorials

Most software tutorials are tragically flawed.

Tutorials often forget to mention some key detail that prevents readers from replicating the author’s process. Other times, the author brings in hidden assumptions that don’t match their readers’ expectations.

The good news is that it’s easier than you think to write an exceptional software tutorial. You can stand out in a sea of mediocre guides by following a few simple rules.

Rules🔗

- Write for beginners

- Promise a clear outcome in the title

- Explain the goal in the introduction

- Show the end result

- Make code snippets copy/pasteable

- Use long versions of command-line flags

- Separate user-defined values from reusable logic

- Spare the reader from mindless tasks

- Let computers evaluate conditional logic

- Keep your code in a working state

- Boil it down to the essentials

- Don’t try to look pretty

- Minimize dependencies

- Specify filenames clearly

- Use consistent, descriptive headings

- Demonstrate that your solution works

- Link to a complete example

Write for beginners🔗

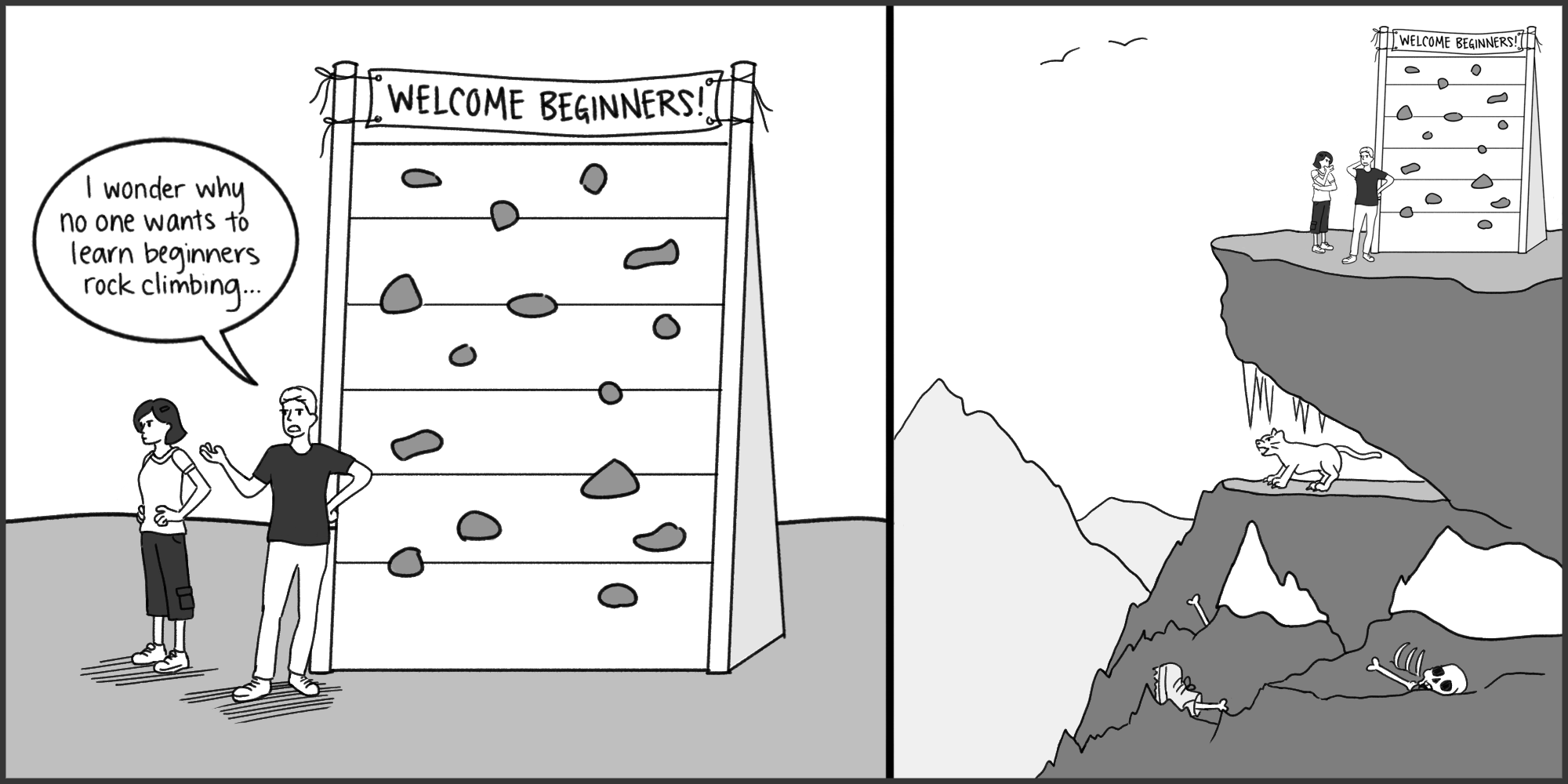

The most common mistake tutorials make is explaining beginner-level concepts using expert-level terminology.

Most people who seek out tutorials are beginners. They may not be beginners to programming, but they’re beginners to the domain they’re trying to learn about.

In this tutorial, I’ll show you how to create your first “Hello world” SPA using React.

Open the included hello.jsx file and change the greeting from "Hello world" to "Hello universe".

The browser should hot reload with the new text. Because of React’s efficient JSX transpilation, the change feels instant.

The browser doesn’t even have to soft reload the page because React’s reconciliation engine compares the virtual DOM to the rendered DOM and updates only the DOM elements that require changes.

The above example would confuse and alienate beginners.

A developer who’s new to the React web framework won’t understand terms like “JSX transpilation” or “reconciliation engine.” They probably also won’t understand “SPA,” “soft reload,” or “virtual DOM” unless they’ve worked with other JavaScript frameworks.

When you’re writing a tutorial, remember that you’re explaining things to a non-expert. Avoid jargon, abbreviations, or terms that would be meaningless to a newcomer.

Here’s an introduction to a React tutorial that uses language most readers will understand, even if they have no background in programming:

In this tutorial, I’ll show you how to create a simple webpage using modern web development tools.

To generate the website, I’m using React, a free and popular tool for building websites.

React makes it easy to create your first website, but it’s also full-featured and powerful enough to build sophisticated apps that serve millions of users.

Writing for beginners doesn’t mean alienating everyone with more experience. A knowledgeable reader can scan your tutorial and skip the information they already know, but a beginner can’t read a guide for experts.

Promise a clear outcome in the title🔗

If a prospective reader is Googling a problem, would the title of your article lead them to the solution? If they see your tutorial on social media or in a newsletter, will your title convince them it’s worth clicking?

Consider the following weak titles:

- A Complete Guide to Becoming a Python CSV Ninja

- How to Build Your Own Twitter

- Key Mime Pi: A Cool Gadget You Can Make

- How to Combine Django with Front-End JavaScript

The above examples are poor titles because they’re vague. From the title alone, you’d be hard-pressed to say what the tutorial will teach you.

A tutorial’s title should explain succinctly what the reader can expect to achieve by following your guide.

Here are clearer rewrites of the previous titles:

- How to Read a CSV File in Python

- Build a Real-Time Twitter Clone in 15 Minutes with Phoenix LiveView

- Key Mime Pi: Turn Your Raspberry Pi into a Remote Keyboard

- Organizing Your Front-End Codebase in a Django Project

These titles give you a clear sense of what you’d learn by reading the tutorial. The titles are clear and specific in what the tutorial delivers.

Explain the goal in the introduction🔗

If the reader clicks your tutorial, you’re off to a great start. Someone is interested in what you have to say. But you still have to convince them to continue reading.

As the reader begins a tutorial, they’re trying to answer two critical questions as quickly as possible:

- Should I care about this technology?

- If I care, is this the right tutorial for me?

The first few sentences of your article should answer those questions.

For example, if you were writing a tutorial about how to use Docker containers, this would be a terrible introduction:

An Introduction to Docker Containers🔗

Docker is an extremely powerful and versatile technology. It allows you to run your app in a container, which means that it’s separate from everything else on the system.

In this tutorial, I’ll show you how to use Docker to run containers on your internal infrastructure as well as in the cloud.

Based on the above introduction, what problem does Docker solve? Who should use it?

The introduction fails to answer those questions and instead hand-waves with vague terms that ignore anything the reader cares about.

Here’s a rewrite that explains how Docker solves pain points the reader might have:

How to Use Docker for Reliable App Deployments🔗

Do you have a production server that you’re terrified to touch because nobody knows how to rebuild it if it goes offline? Have you ever torn your hair out trying to figure out why your staging environment behaves differently than your production environment?

Docker is a tool for packaging your app so that it has a consistent, reproducible environment wherever it runs. What’s more, it allows you to define your app’s environment and dependencies in source code, so you know exactly what’s there, even if your app has survived years of tweaks by different teams.

In this tutorial, I’ll show you how to use Docker to package a simple web app and help you avoid common Docker gotchas.

The above introduction explains the problems Docker solves and what the tutorial will deliver.

The introduction doesn’t say, “This tutorial is for people who are brand new to Docker,” but it doesn’t need to. It introduces Docker as a new concept, which tells the reader that the guide is for newcomers.

Show the end result🔗

As soon as possible, show a working demo or screenshot of what the reader will create by the end of your tutorial.

The end result doesn’t have to be anything visually stunning. Here’s an example of how I showed the terminal UI the user would see at the end of my tutorial:

Early in your tutorial, show the reader a preview of what they’ll produce by the end.

Showing the final product reduces ambiguity about your goal. It helps the reader understand if it’s the right guide for them.

Make code snippets copy/pasteable🔗

As the reader follows your tutorial, they’ll want to copy/paste your code snippets into their editor or terminal.

An astonishing number of tutorials unwittingly break copy/paste functionality, making it difficult for the reader to follow along with their examples.

Make shell commands copyable🔗

One of the most common mistakes authors make in code snippets is including the shell prompt character.

A shell snippet with leading $ characters will break when the user tries to paste it into their terminal.

$ sudo apt update # <<< Don't do this!

$ sudo apt install vim # <<< Users can't copy/paste this sequence without

$ vim hello.txt # << picking up the $ character and breaking the command.

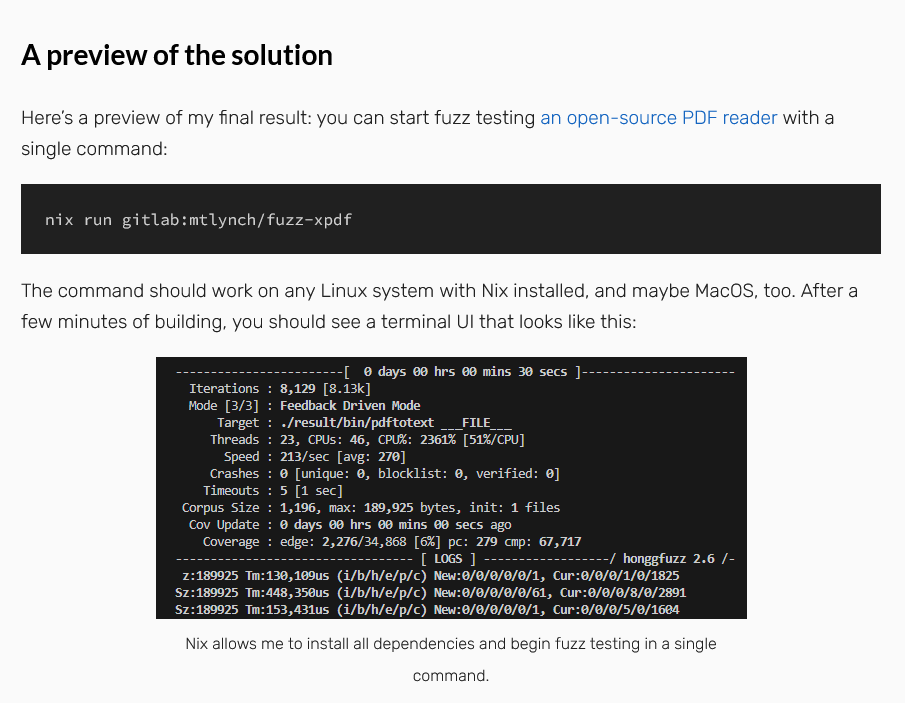

Even Google gets this wrong. In some places, their documentation helpfully offers a “Copy code sample” button.

Google offers a “Copy code sample” button that incorrectly copies shell terminal characters.

If you click the copy button, it copies the $ terminal prompt character, so you can’t paste the code:

michael@ubuntu: $ gcloud services enable pubsub.googleapis.com

$ gcloud services disable pubsub.googleapis.com

bash: $: command not found

bash: $: command not found

michael@ubuntu:

There’s a different version of this copy/paste error that’s more subtle:

sudo apt update

sudo apt install software-properties-common

sudo add-apt-repository ppa:deadsnakes/ppa

sudo apt install python3.9

If I try to paste the above snippet, here’s what I see in the terminal:

0 upgraded, 89 newly installed, 0 to remove and 2 not upgraded.

Need to get 36.1 MB of archives.

After this operation, 150 MB of additional disk space will be used.

Do you want to continue? [Y/n] Abort.

$

What happened?

When the apt install software-properties-common command executes, it prompts the user for input. The user can’t answer the prompt because apt just continues reading from the clipboard paste.

Most command-line tools offer flags or environment variables to avoid forcing the user to respond interactively. Use non-interactive flags to make command snippets easy for the user to paste into their terminal.

sudo apt update

sudo apt install --yes software-properties-common

sudo add-apt-repository --yes ppa:deadsnakes/ppa

sudo apt install --yes python3.9

Join shell commands with &&🔗

Take another look at the Python installation example I showed above, as it has a second problem:

sudo apt update

sudo apt install software-properties-common

sudo add-apt-repository ppa:deadsnakes/ppa

sudo apt install python3.9

If one of the commands fails, the user might not notice. For example, if the first command was sudo apt cache ppa:dummy:non-existent, that command would fail, but the shell would happily execute the next command as if everything was fine.

In most Linux shells, you can join commands with && and continue lines with a backslash. That tells the shell to stop when any command fails.

Here’s the user-friendly way to include a series of copy-pasteable commands:

&&sudo apt update && \

sudo apt install --yes software-properties-common && \

sudo add-apt-repository --yes ppa:deadsnakes/ppa &&

sudo apt install --yes python3.9

The user can copy/paste the entire sequence without having to tinker with it in an intermediate step. If any of the commands fail, the sequence stops immediately.

Only show the shell prompt to demonstrate output🔗

Occasionally, showing the shell prompt character benefits the reader.

If you show a command and its expected output, the shell prompt character helps the reader distinguish between what they type and what the command returns.

For example, a tutorial about the jq utility might present results like this:

The jq utility allows you to restructure JSON data elegantly:

$ curl \

--silent \

--show-error \

https://status.supabase.com/api/v2/summary.json | \

jq '.components[] | {name, status}'

{

"name": "Analytics",

"status": "operational"

}

{

"name": "API Gateway",

"status": "operational"

}

...

Exclude line numbers from copyable text🔗

It’s fine to include line numbers alongside your code snippets, but make sure they don’t break copy/paste. For example, if the user tries to copy the count_tables function from the following snippet, they’d have to remove line numbers from their pasted text.

123 def count_tables(form):

124 if not form:

125 return None

Use long versions of command-line flags🔗

Command-line utilities often have two versions of the same flag: a short version and a long version.

-r / --recursive : Run recursively

^ ^

| |

| long flag

|

short flag

Always use long flags in tutorials. They’re more descriptive, so they make your code easier to read, especially for beginners.

Run the following command to find all the pages with <span> elements:

grep -i -o -m 2 -r '<span.*</span>' ./

Even if the reader is familiar with the grep tool, they probably haven’t memorized all of its flags.

Use long flags to make your examples clear to both experienced and inexperienced readers.

Run the following command to find all the pages with <span> elements:

grep \

--ignore-case \

--only-matching \

--max-count=2 \

--recursive \

'<span.*</span>' \

./

Separate user-defined values from reusable logic🔗

Often, a code example contains elements that are inherent to the solution and elements that each reader can customize for themselves. Make it clear to the reader which is which.

The distinction between a user-defined value and the rest of the code might seem obvious to you, but it’s unclear to someone new to the technology.

Use environment variables in command-line examples🔗

A logging service that I use lists the following example code for retrieving my logs on the command line:

LOGS_ROUTE="$(

curl \

--silent \

--header "X-Example-Token: YOUR-API-TOKEN" \

http://api.example.com/routes \

| grep "^logs " \

| awk '{print $2}'

)" && \

curl \

--silent \

--header "X-Example-Token: YOUR-API-TOKEN" \

"http://api.example.com${LOGS_ROUTE}" \

| awk \

-F'T' \

'$1 >= "YYYY-MM-DD" && $1 <= "YYYY-MM-DD" {print $0}'

Given that example, which values am I supposed to replace?

Clearly, YOUR-API-TOKEN is a placeholder that I need to replace, but what about YYYY-MM-DD? Am I supposed to replace it with real dates like 2024-11-23? Or is it specifying a date schema, meaning that YYYY-MM-DD is the literal value I’m supposed to keep?

There are several other numbers and strings in the example. Do I need to replace any of those?

Instead of forcing the reader to search through your example and guess which values to change, create a clean separation. Start with the editable values, then give them the snippet they can copy/paste verbatim.

Here’s my rewrite of the example above:

API_TOKEN='YOUR-API-KEY' # Replace with your API key.

START_DATE='YYYY-MM-DD' # Replace with desired start date.

END_DATE='YYYY-MM-DD' # Replace with desired end date.

LOGS_ROUTE="$(

curl \

--silent \

--header "X-Example-Token: $API_TOKEN" \

http://api.example.com/routes \

| grep "^logs " \

| awk '{print $2}' \

)" && \

curl \

--silent \

--header "X-Example-Token: $API_TOKEN" \

"http://api.example.com${LOGS_ROUTE}" \

| awk \

-F'T' \

-v start="$START_DATE" \

-v end="$END_DATE" \

'$1 >= start && $1 <= end {print $0}'

The new version distinguishes between values the reader must replace and code that must remain in place.

Using environment variables clarifies the intent of the user-defined values and means the user only has to enter each unique value once.

Use named constants in source code🔗

Suppose that you were writing a tutorial that demonstrated how to crop an image so that it displays well in social sharing cards on Bluesky, Twitter, and Facebook:

The image in the post above has image dimensions specifically to fit social sharing cards.

Here’s how you might show code for cropping an image to fit social media cards:

func CropForSocialSharing(img image.Image) image.Image {

targetWidth := 800

targetHeight := int(float64(targetWidth) / 1.91)

bounds := img.Bounds()

x := (bounds.Max.X - targetWidth) / 2

y := (bounds.Max.Y - targetHeight) / 2

rgba := image.NewRGBA(

image.Rect(x, y, x+targetWidth, y+targetHeight))

draw.Draw(

rgba, rgba.Bounds(), img, image.Point{x, y}, draw.Src)

return rgba

}

The example shows four numbers:

8001.9122(again)

Which numbers are the reader free to change?

In source code examples, make it obvious which values are inherently part of the solution and which are arbitrary.

Consider this rewrite that makes the intent of the numbers clearer:

// Use a 1.91:1 aspect ratio, which is the dominant ratio

// on popular social networking platforms.

const socialCardRatio = 1.91

func CropForSocialSharing(img image.Image) image.Image {

// I prefer social cards with an 800px width, but you can

// make this larger or smaller.

targetWidth := 800

// Choose a height that fits the target aspect ratio.

targetHeight := int(float64(targetWidth) / socialCardRatio)

bounds := img.Bounds()

// Keep the center of the new image as close as possible to

// the center of the original image.

x := (bounds.Max.X - targetWidth) / 2

y := (bounds.Max.Y - targetHeight) / 2

rgba := image.NewRGBA(

image.Rect(0, 0, targetWidth, targetHeight))

draw.Draw(

rgba, rgba.Bounds(), img, image.Point{x, y}, draw.Src)

return rgba

}

In this example, the code puts the value of 1.91 in a named constant and has an accompanying comment explaining the number. That communicates to the reader that they shouldn’t change the value, as it will cause the function to create images with poor proportions for social sharing cards.

On the other hand, the value of 800 is more flexible, and the comment makes it obvious to the reader that they’re free to choose a different number.

Spare the reader from mindless tasks🔗

The reader will appreciate your tutorial if you show that you respect their time.

Don’t force the reader to perform tedious interactive steps when a command-line snippet would achieve the same thing.

Do the following tedious steps:

- Run

sudo nano /etc/hostname - Erase the hostname

- Type in

awesomecopter - Hit Ctrl+o to save the contents

- Hit Ctrl+x to exit the editor

The above steps make your tutorial boring and error-prone. Who wants to waste mental cycles manually editing a text file?

Instead, show the reader a command-line snippet that achieves what they need:

Paste the following simple command:

echo 'awesomecopter' | sudo tee /etc/hostname

Let computers evaluate conditional logic🔗

I’m always disappointed when a tutorial transforms into a “Choose Your Own Adventure”-style book, except I have to choose based on conditions of my OS environment:

If you’re on Debian 10, run this command.

sudo apt install --yes example-package-legacy

If you’re on Debian 11, run this command:

sudo apt install --yes example-package

If you’re on Debian 12, run this command:

sudo apt install --yes example-package2

I don’t want to keep searching through a list of possible commands and picking out the one for me.

You know who’s great at evaluating conditional logic? Computers! It’s what they do all day long. They love it. So, let them do it.

Run the following snippet to install the right version of example-package for your system:

if [ -f /etc/os-release ]; then

. /etc/os-release

if [ "$ID" = "debian" ]; then

case "$VERSION_ID" in

"10") sudo apt install --yes example-package-legacy ;;

"11") sudo apt install --yes example-package ;;

"12") sudo apt install --yes example-package2 ;;

*) echo "ERROR: Unsupported platform" ;;

esac

else

echo "ERROR: Unsupported platform"

fi

else

echo "ERROR: Unsupported platform"

fi

If you’re not a shell scripting whiz, use an LLM like Anthropic Claude or Meta Llama to generate a shell snippet. Even free, low-powered LLMs can do this accurately.

Keep your code in a working state🔗

Some authors design their tutorials the way you’d give instructions for an origami structure. It’s a mysterious sequence of twists and folds until you get to the end, and then: wow, it’s a beautiful swan!

A grand finale might be fun for origami, but it’s stressful for the reader.

Give the reader confidence that they’re following along correctly by keeping your example code in a working state.

Here’s some example code, but don’t even think about compiling it. It’s missing the parseOption function LOL!

// example.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#define MAX_LINE_LENGTH 256

int main() {

char line[MAX_LINE_LENGTH];

char key[MAX_LINE_LENGTH];

char value[MAX_LINE_LENGTH];

while (fgets(line, sizeof(line), stdin)) {

// Don't do this!

parseOption(line, key, value); // <<< Not yet defined

printf("Key: '%s', Value: '%s'\n", key, value);

}

return 0;

}

If the reader tries to compile the above example, they get an error:

$ gcc example.c -o example

example.c: In function ‘main’:

example.c:14:7: warning: implicit declaration of function ‘parseOption’

[-Wimplicit-function-declaration]

14 | parseOption(line, key, value); // <<< Not yet defined

| ^~~~~~~~~~~

/usr/bin/ld: /tmp/ccmLGENX.o: in function `main':

example.c:(.text+0x2e): undefined reference to `parseOption'

collect2: error: ld returned 1 exit status

As early as possible, show the reader an example they can play with. Build on that foundation while keeping the code in a working state.

// example.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#define MAX_LINE_LENGTH 256

void parseOption(char *line, char *key, char *value) {

// Fake the parsing part for now.

strncpy(key, "not implemented", MAX_LINE_LENGTH - 1);

strncpy(value, "not implemented", MAX_LINE_LENGTH - 1);

}

int main() {

char line[MAX_LINE_LENGTH];

char key[MAX_LINE_LENGTH];

char value[MAX_LINE_LENGTH];

while (fgets(line, sizeof(line), stdin)) {

parseOption(line, key, value);

printf("Key: '%s', Value: '%s'\n", key, value);

}

return 0;

}

Now, I test the program to see that it runs:

$ gcc example.c -o example && \

printf 'volume:25\npitch:37' | \

./example

Key: 'not implemented', Value: 'not implemented'

Key: 'not implemented', Value: 'not implemented'

The code fakes parsing options for now, but the dummy code confirms that everything else is working.

Keeping your code in a working state gives the reader confidence that they’re following along correctly. It frees them from the worry that they’ll waste time later retracing their steps to find some minor error.

Boil it down to the essentials🔗

A good tutorial should explain one thing and explain it well.

A common mistake is to claim a tutorial is about a particular topic, and then bury the lesson in a hodgepodge of unrelated technologies.

In this tutorial, I’ll show you how to add client-side search to your Hugo blog so that readers can do instant, full-text search of all your blog posts, even on spotty mobile connections.

But that’s not all!

While I’m showing full-text search, I’ll simultaneously demonstrate how you can use browser local storage to store your user’s search history and then use an expensive AI service to infer whether the user prefers your website’s dark mode or light mode UI theme.

In the example above, the tutorial starts by promising something many readers want: full-text search of a blog.

Immediately after promising full-text search, the tutorial layers in a grab bag of unrelated ideas. Now, anyone interested in full-text search has to untangle the search concepts from everything else.

People come to a tutorial because they want to learn one new thing. Let them learn that one thing in isolation.

In this tutorial, I’ll show you how to add client-side search to your Hugo blog so that readers can do instant, full-text search of all your blog posts, even on spotty mobile connections.

That’s the only thing I’ll demonstrate in this tutorial.

If you have to stack technologies, wait until the end🔗

Sometimes, a tutorial has to combine technologies.

For example, the PHP web programming language doesn’t have a production-grade web server built-in. To demonstrate how to deploy a PHP app to the web, you’d have to choose a server like Apache, nginx, or Microsoft IIS. No matter which server technology you choose, you alienate readers who prefer a different web server.

If you have to combine concepts, defer it to the end. If you’re teaching PHP, take the tutorial as far as you can go using PHP’s development server. If you show how to deploy the PHP app in production using nginx, push those steps to the end so everyone who prefers a different web server can follow everything in your tutorial until the web server portion.

Don’t try to look pretty🔗

Here’s an excerpt from an article I read recently. Can you guess what type of tutorial it was?

<div class="flex flex-row mb-4 overflow-hidden bg-white">

<div class="flex flex-col w-full p-6 text-light-gray-500">

<div class="flex justify-between mb-3">

<span class="uppercase">{{ title }}</span>

</div>

<slot></slot>

</div>

</div>

If you guessed that I was reading a tutorial about a CSS framework, you’d be wrong.

The above snippet was from a tutorial about using the <slot> element in the Vue web framework. So, why was half the code just CSS classes? The author added them to make their example look pretty.

Here’s the same snippet as above, reduced to the code necessary to convey the concept:

<div class="card">

<p class="card-title">{{ title }}</p>

<slot></slot>

</div>

The simplified code doesn’t generate a beautiful browser-friendly card, but who cares? It sets a clear foundation to explain the <slot> element without distracting you with unrelated technology.

Readers don’t care if your toy application looks beautiful. They want a tutorial that makes new concepts obvious.

Minimize dependencies🔗

Every tutorial has dependencies. At the very least, the reader needs an operating system, but they likely also need a particular compiler, library, or framework to follow your examples.

Every dependency pushes work onto the reader. They need to figure out how to install and configure it on their system, which reduces their chances of completing your tutorial.

Make your tutorial easy on the reader by minimizing the number of dependencies it requires.

We’re at step 12 of this tutorial, so it’s time to install a bunch of annoying packages I didn’t mention earlier:

- ffmpeg, compiled with the libpita extension (precompiled binaries are not available)

- A special fork of Node.js that my friend Slippery Pete published in 2010 (you’ll need Ubuntu 6.06 to compile it)

- Perl 4

The most common and frivolous dependencies I see are date parsing libraries. Have you seen instructions like this?

The CSV file contains dates in YYYY-MM-DD format. To parse it, install this 400 MB library designed to parse any date string in any format, language, and locale.

You never need a whole third-party library to parse a simple date string in example code. At worst, you can parse it yourself with five lines of code.

Beyond making your guide harder to follow, each dependency also decreases your tutorial’s lifespan. In a month, the external library might push an update that breaks your code. Or the publisher could unpublish the library, and now your tutorial is useless.

You can’t always eliminate dependencies, so use them strategically. If your tutorial resizes an image, go ahead and use a third-party image library instead of reimplementing JPEG decoding from scratch. But if you can save yourself a dependency with less than 20 lines of code, it’s almost always better to keep your tutorial lean.

Pin your dependencies to specific versions🔗

Be explicit about which versions of tools and libraries you use in your tutorial. Libraries publish updates that break backward compatibility, so make sure the reader knows which version you confirmed as working.

Install a stable version of Node.js

Install Node.js 22.x. I tested this on Node.js v22.12.0 (LTS).

Specify filenames clearly🔗

My biggest pet peeve in a tutorial is when it casually instructs me to “add this line to your configuration file.”

Which configuration file? Where?

To enable tree-shaking, add this setting to your config file:

optimization: {

usedExports: true,

minimize: true

}

If the reader needs to edit a file, give them the full path to the file, and show them exactly which line to edit.

There are plenty of ways to communicate the filename: in a code comment, in a heading, or even in the preceding paragraph. Anything works as long as it unambiguously shows the user where to make the change.

To enable tree-shaking, add the following optimization setting to your Webpack configuration file under module.exports:

// frontend/webpack.config.js

module.exports = {

mode: "production",

entry: "./index.js",

output: {

filename: "bundle.js",

},

// Enable tree-shaking to remove unused code.

optimization: {

usedExports: true,

minimize: true,

},

};

Use consistent, descriptive headings🔗

Most readers skim a tutorial before they decide to read it in detail. Skimming helps the reader assess whether the tutorial will deliver what they need and how difficult it will be to follow.

If you omit headings, your tutorial will intimidate the reader with a giant wall of text.

Instead, use headings to structure your tutorial. A 25-step tutorial feels friendlier if you structure it as a five-step tutorial in which each step has four to six substeps.

Write clear headings🔗

It’s not enough to stick a few headings between long stretches of text.

Think about the wording of the headings so that they communicate as much as possible without sacrificing brevity.

Which of these tutorials would you rather read?

- Go

- Installation

- Hello, world!

- Deployment

Or this?

- Why Choose Go?

- Install Go 1.23

- Create a Basic “Hello, World” Go App

- Deploy your App to the Web

The second example communicates more information to the reader and helps them decide if this is the right tutorial for them.

Make your headings consistent🔗

Before you publish your tutorial, review your headings for consistency.

- How I Installed Go 1.23

- Step 2: Your First App

- How I package Go apps

- Part D: How you’ll deploy your App

When reviewing your headings, check for consistency in the following:

- Casing

- Do your headings use title casing or sentence casing?

- Point of view

- Are the steps presented as “I did X,” “You do X,” or neutral?

- Verb tense

- Are you using present tense, past tense, or future tense?

Create a logical structure with your headings🔗

Ensure that your headings reflect a logical structure in your tutorial.

I often see tutorials where the headings create a nonsensical structure.

- Why Go?

- The history of nginx

- Configuring nginx for local access

- Creating your First Go app

- Why Go is better than Perl

- Serve a basic page

In the example above, the heading “Why Go?” has a subheading of “The history of nginx,” even though nginx’s history isn’t a logical subtopic of Go.

Demonstrate that your solution works🔗

If your tutorial teaches the reader how to install a tool or integrate multiple components, show how to use the result.

Finally, run this command to enable the nginx service:

sudo systemctl enable nginx

Congratulations! You’re done!

I assume that you know how to do everything from here, so I offer no further guidance.

If you explain how to install something, use the result to show the reader how it works.

Your example can be as simple as printing out the version string. Just show how to use the tool for something so that the reader knows whether or not the tutorial worked.

Finally, run this command to enable the nginx service:

sudo systemctl enable nginx

Next, visit this URL in your browser:

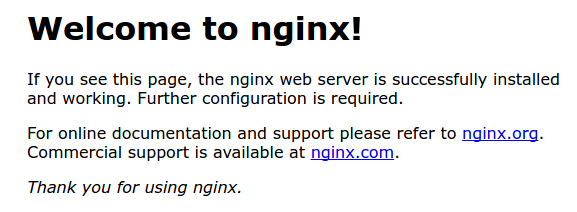

If everything worked, you should see the default nginx success page.

The nginx success page

In the following sections, I’ll show you how to replace nginx’s default webpage and configure nginx’s settings for your needs.

Link to a complete example🔗

Even if you’re diligent about keeping the reader oriented throughout the tutorial, it still helps to show how everything fits together.

Link the reader to a code repository that contains all the code you demonstrated in your tutorial.

Ideally, the repository should run against a continuous integration system such as CircleCI or GitHub Actions to demonstrate that your example builds in a fresh environment.

Bonus: Show the complete code at each stage🔗

I like to split my repository into git branches so that the reader can see the complete state of the project at every step of the tutorial, not just the final result.

For example, in my tutorial, “Using Nix to Fuzz Test a PDF Parser,” I show the reader the earliest buildable version of the repository in its own branch:

At the end of the tutorial, I link to the final result:

If your tutorial involves files that are too large to show for each change, link to branches to show how the pieces of your tutorial fit together.

Illustration by Loraine Yow.

I often see developers make mistakes in their tutorials that trip up readers, so I thought a lot about what makes some tutorials effective and what makes others frustrating.

— Michael Lynch (@mtlynch.io) Jan 2, 2025 at 10:18 AM

[image or embed]